Pancreatic cancer surgery

The most common treatment for early stage pancreatic cancer is surgery to remove the cancer.

It is usually followed by chemotherapy and sometimes radiotherapy. Some people may receive chemotherapy, with or without radiotherapy, before surgery to shrink the tumour and increase the chances of complete removal during surgery.

In advanced pancreatic cancer, when the cancer has spread to other areas of the body, surgery to remove the cancer is usually not an option. Surgery can however be used to relieve symptoms caused by the pancreatic tumour.

Types of surgery to remove a pancreatic tumour

About 25% of people with pancreatic cancer will have surgery. Depending on where the cancer is, you may have one of the following operations:

Distal pancreatectomy

The tail and/or a portion of the body of the pancreas are removed, but not the head, with or without removal of the spleen (splenectomy) for tumours in the tail of the pancreas.

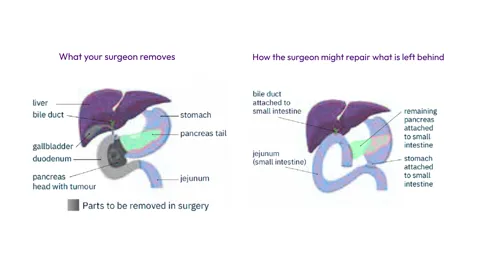

Whipple procedure

Taking out part of your pancreas (usually the head of the pancreas), your duodenum (the first part of your small bowel), your gallbladder and part of your bile duct as well as removing a small part of your stomach.

Total pancreatectomy

Removal of the whole pancreas as well as your duodenum, part of the stomach, the gallbladder and part of your bile duct, the spleen and many of the surrounding lymph nodes.

For all surgeries, Pankind recommends you choose a high volume centres as higher volume surgeons have improved outcomes.

The Whipple procedure is the most common type of pancreatic cancer surgery. It is major surgery and performed by a specialised pancreatic or hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) surgeon. The surgeon will remove the head, or right-hand portion, of the pancreas, which is where most tumours happen. Because of the difficult location of the pancreas, the surgeon will also have to remove part of the small intestine, gallbladder, bile duct and sometimes a part of the stomach.

In recent years, a new procedure using robotic surgery has been used in some hospitals to perform Whipple procedure. This surgery is more advanced and less invasive than using the usual laparoscopic keyhole surgery. However, robotic surgery and keyhole surgery are relatively new techniques and won’t be available in all cancer centres. We need further research in the area before we are sure of their benefits.

Whipple procedure

Preparing for surgery

Your treatment team will inform you about any tests you need to have prior to surgery. This will usually include tests to determine your general health and fitness for such a big operation. You may need to have all or some of the following:

● blood tests to check general health, tumour markers (CA19-9) and kidney and liver function

● breathing tests and possibly a chest x-ray to check your lungs are okay

● electrocardiogram and echocardiogram to check your heart is functioning well.

You will need to have an appointment at a pre-hospital admission clinic. This may be a few days or a week before your operation. The order in which things happen may vary between hospitals. At this session you may see:

● your surgeon, to discuss the exact operation, its benefits and possible complications, as well as consenting to the operation

● nurses, to discuss your general health, recovery in hospital and what you will need when you go home

● a physiotherapist, to teach leg and breathing exercises you need to do before and after surgery to prevent blood clots and infections

● an anaesthetist, to assess you before the operation to make sure you are fit enough to have a long anaesthetic

● a dietitian, to discuss the possible dietary problems after surgery and what can be done to help manage your diet. It’s not uncommon to lose weight after major abdominal surgery. A dietitian will also help you get as well as possible before your operation and provide useful tips on how to increase your overall nutrition. This may include drinking some nutritional supplements before your operation.

Before your operation, your doctors and nurses may suggest you make an advance care plan. This allows you to set out in writing your wishes for all your future medical care. Advance care plans are the best way to make sure important decisions about your care are carried out in the way you want them to be. You may also be asked to fill in a form called ‘medical orders for life-sustaining treatment’ and/or a ‘goals of care’ form. These forms allow you to express your preferences about your ongoing care and life sustaining treatments.

After surgery

Surgery to remove pancreatic cancer is complex. It can take several hours to perform (between five and 12 hours), and you will be in hospital for one to two weeks if there are not any complications.

Immediately after your operation you may be in an intensive care unit. This is so a team of doctors and nurses can monitor you very closely.

● You will need to have regular pain relief. Your doctors and nurses will want you to be as pain free as possible during your recovery time.

● You will have several drips and tubes in place to help keep your body hydrated and fed until you can return to eating normal food. You may also have some tubes draining blood or fluid. A urinary catheter will be inserted before the operation and removed a few days after your operation.

● You may need to take pancreatic enzyme tablets after the operation. Your surgeon will discuss this with you. These are taken with each meal and help to digest fat and proteins.

● You may develop diabetes. Because the pancreas produces insulin, you may develop diabetes if you have part or all your pancreas removed. This means you will need to have regular insulin injections. This will be managed by the endocrinology team.

● If you have your spleen taken out, you will be more susceptible to infection and your blood clotting mechanisms may be affected. You may find it helpful to refer to Spleen Australia for further information about having a splenectomy.

You are likely to be in hospital for about 10‒14 days. But if you develop any complications you may need to stay longer.

Possible complications after surgery for pancreatic cancer

After any operation there are risks and possible complications which can make recovery more difficult. Surgery to treat pancreatic cancer carries some serious risks.

It is important you and your doctor discuss the pros and cons of the surgery prior to the operation. A decision to go ahead with this type of surgery is based on your health, the size and location of your tumour and the risks involved.

About 4 out of 10 (40%) people who have pancreatic surgery will develop one or more complications, and this can vary between hospitals and states. Some complications are minor, while others can be serious.

Possible complications and long-term issues following surgery include:

Major internal bleeding after surgery is rare. But if it happens you may need to have a blood transfusion or have urgent surgery to stop the bleeding.

Anastomotic leak after surgery is a serious complication and happens in about 1 in 10 cases. This happens if the join (anastomosis) between the part of your pancreas that is left behind and your small bowel leaks. This means pancreatic digestive juices leak into your abdominal cavity. This is a serious problem as it can cause infections and, if not treated, death. Antibiotics and draining the fluid are options but sometimes it may mean further surgery.

Bowel paralysis (ileus) is when your bowel stops working for a few days, which often happens after major surgery. You will feel nauseous, bloated and uncomfortable in your stomach area. Treatment for this is to put a tube through your nose into your stomach (naso-gastric tube) and give you intravenous fluids until your bowel starts working again. The tube into your stomach is used to suction out extra air or material that you would otherwise vomit.

Also called gastroparesis, delayed gastric emptying means the slowing or stopping of the movement of food from your stomach to your small intestine. It is a common problem after pancreatic surgery. It affects between 14% and 30% of people after surgery. You will not be able to eat until the situation improves. Delayed gastric emptying is not life threatening but it can mean a longer stay in hospital.

Blood clots (also known as deep vein thrombosis or DVT) can occur after surgery as you are resting and not moving around much. A DVT will block normal blood flow through your veins. There is a chance it will dislodge from its position and travel to the lungs. This can be fatal if it causes a blockage in the lungs (pulmonary embolism).

To try to prevent blood clots, you may have daily injections of blood-thinning medication, physiotherapy and wear anti-embolic stockings. You may have to continue using these for short time once you are at home. Moving around soon after surgery can greatly help with preventing clots.

Infections can occur in the chest and surgical wound, and there may be leakage of bile internally around the operation site. Urinary tract infections caused by having a catheter or infections from other tubes used to give you fluids and medications (e.g. Intravenous cannula) are also a risk. You will have antibiotics during and after surgery to try and prevent any of these infections. Physiotherapy and moving around as soon as possible after the operation can also help prevent chest infections and pneumonia. If bile or other fluids leak from the surgical wound, it may need to be drained. It is very important to prevent any internal/external fluid leakages, otherwise it could mean further treatment and a longer hospital stay.

Diarrhoea can happen because part of the pancreas is taken out during surgery and the part that remains may not be able to produce enough enzymes to properly help with food digestion and fat absorption from food. Undigested fat can cause diarrhoea.

Your dietitian and nurses will discuss ways to help you cope. You will most likely need to take a pancreatic exocrine supplement (see ‘Managing symptoms and side effects’).

Constipation can happen after surgery. It can take some time for the bowel to start working after you begin to eat again. The drugs used to help control your pain after surgery can also cause constipation. A specialist dietitian can help.

Diabetes can happen because the food pathway through your gut is shortened and food can pass through your small intestine quickly, causing diarrhoea and poor digestion of food. It may also occur if all or part of your pancreas has been removed, or the part of your pancreas that is left is scarred from inflammation caused by the tumour.

With advances in surgery, death after pancreatic surgery is now very rare. It is still a risk. If you have a very experienced surgeon perform your operation at a specialised centre that does a large volume of cases each year, the death rates are very low (1‒2%). This is why we suggest asking your surgeon how many operations were done at the hospital in the previous year, before deciding on where you will have your operation. We know that international guidelines state higher volume centres and higher volume surgeons have improved outcomes. Your GP will likely be a helpful and reassuring support for you if you need help asking this question.

Going home after your operation

It can take between 6 and 12 weeks to recover from surgery for pancreatic cancer.

During your recovery at home, it is important to gently exercise to help build up your strength. Before you go home, your doctor and physiotherapist will advise you about the amount of exercise and best type of exercise for you. Gentle walking and swimming after all the wounds have healed are often helpful.

You may have a community nurse visit you at home for a while after your operation. They will dress any wounds you have and help you with hygiene needs.

If you have any concerns at home, contact the hospital, specialist nurse (if you have one) or your GP. Always keep these numbers close by.

Make an appointment to see your GP soon after you are discharged from hospital. Your GP will play an important role in working as part of your multidisciplinary team to monitor you and ensure you are well supported.

At this stage, almost three years since my Whipple surgery, I feel 85% back to where I might have been otherwise.

- Tom

Types of surgery to relieve symptoms

Surgery can be used to relieve the symptoms caused by a pancreatic tumour, such as jaundice, a bowel blockage and pain.

Jaundice is a condition that happens due to a blockage in the bile duct. If this happens you may:

● feel sick (nauseous) and vomit

● feel very itchy, weak and tired

● have pain or discomfort in your abdominal area.

● get a yellow colour in your skin and the whites of your eyes.

These symptoms can happen with localised disease, but they can also happen if your cancer is advanced and curative surgery isn’t an option. Your doctor may decide to put a small tube (stent) into the bile duct to hold the duct open and relieve the blockage. This can be done using an endoscope and is usually successful.

If you can’t have a stent, or it hasn’t been successful (which is rare), your specialist may do it radiologically (percutaneous transhepatic approach), or suggest an operation called a choledochojejunostomy or hepaticojejunostomy. This means cutting the bile duct above the blockage and then reconnecting it to the small bowel. This allows bile to bypass the blocked bile duct and drain out. Although recovering from an operation can be challenging, it is usually worth it, as it almost always relieves the jaundice and other symptoms.

Sometimes the pancreatic cancer causes a partial or complete bowel blockage (obstruction) in the small bowel (duodenum). This is a serious problem and can make you feel very sick. Anything you eat or drink can’t pass into the bowel as it normally would. It sits in the stomach and eventually you will vomit it back up again. You may also get cramping pain and swelling in the abdominal area.

To relieve this, your doctor may suggest putting a tube (stent) into the duodenum to keep it open. Or your doctor may recommend an operation to bypass the blockage. You would need to discuss the pros and cons of this operation with your doctor.

Pancreatic cancer can cause intense abdominal pain caused by the tumour pressing on nearby organs. Your doctor may recommend a procedure called a celiac plexus block to help control your pain. This involves an injection to damage the celiac nerves, a bundle of nerves located behind the pancreas. This inhibits your nerves from sending pain messages to your brain and may provide temporary or long-term pain relief. A celiac plexus block can be done during surgery, during an endoscopic ultrasound or by inserting a needle through the skin.

Contact Dianne, Support Navigator

on 1800 003 800 for information and find out about the services and support that may be available for you and your family.

Always consult your doctor or health professional about any health-related matters. Pankind does not provide medical or personal advice and is intended for general informational purposes only. Read our full Terms of Use.

Thank you to the clinicians, researchers, patients, and carers who have helped us create and review our support resources, we could not have done it without you.